Founded 25 years ago, Simpson Street Free Press is a paper made by young people on the South side of Madison.

Amber Walker wrote about Simpson Street in a recent article in The Cap Times:

Simpson Street Free Press started as a free monthly newspaper in the Broadway-Simpson neighborhood on Madison’s south side, just south of Lake Monona, in 1992. Six students from La Follette High School — Keysha McCann, Tammy Washington, Tasha Bell, Patricia Bell, Dee Graham and Tomiko Osbey — wanted a platform for teens to share their thoughts and combat what they saw as negative stereotypes and incomplete coverage about their neighborhood in the mainstream media.

Fannie Mims, president of the now defunct Broadway-Simpson neighborhood association (now called the Bridge-Lakepoint-Waunona neighborhood) and Kramer, a resident and volunteer, served as adult editors for the fledgling paper. They helped the teens hone their voices as they wrote about violence, teen pregnancy, domestic abuse and other issues that were important to them.

By 1998, Simpson Street welcomed teens from all over Madison to write for the paper. Through donations, Kramer and Mims were able to pay students modest stipends for their work, which continues today.

I first heard about Simpson Street Free Press when my middle school librarian handed me its hard-copy newspaper. The Free Press looked like the other newspapers on display, but it was filled with stories written by kids my age who looked kind of like me.

I was bright, but had issues focusing at school. But those issues tended to dissolve when I was allowed to be creative. After starting my own little newsletter in fifth grade, I already fancied myself a newspaper girl; but the school paper at my middle school was shut down due to budget cuts and lack of interest.

I talked with a guidance counselor about how I could get involved in another way. This most-unhelpful counselor did less than the bare minimum. She suggested I talk to some student I didn’t really know about how to get involved. It was middle school, and I gave up.

Later, in high school, I overheard a boy in my English class making fun of the school newspaper for which I proudly wrote and occasionally edited. He told me in no uncertain terms that one of the school newspapers I worked on was “trash.”

I wanted to dismiss what he had to say, but he had a point. There was barely any editorial review. It was maybe a bit self-congratulatory. I pressed him for insights on who the hell he thought he was to expect so much out of a high school paper; he turned around and told me that he took part in a real newsroom experience.

I’m like, Okay, so tell me where it is.

People describe Simpson Street as a sparkling gem on the South Side of Madison, but it’s more than that. Rather, it’s a mirror of the sometimes-unsung bright young minds that make up Dane County and its surrounding areas.

For me, it was a place where my writing talent was recognized, nurtured, and held to very high standards. Rigor and creative freedom coexisted. Staff writers—that’s what they called us—were valued for what knowledge, perspective, brilliance we already brought to the table. I felt respected, and because of that, I grew.

“It’s fun to have something going on in the gym for sports, but we need more academics for our kids,” Adams said. “When it came down to getting him that material (for school) I had to run to Simpson Street Free Press for it.”

—Jewel Adams, as interviewed by Amber C. Walker

At SSFP, my work mattered and meant something to people. I had never been in an environment where my intellect and weirdness could combine to create a generative discussion, or to help someone learn a concept. With these high standards in place, I became a much better writer, and in turn, a much better reader and editor. Without realizing it, I had become a leader.

Multiple rounds of edits from their peers and adults encourage students to refine their craft. The idea is if students are invested in turning in their best work for the paper, that commitment to excellence will benefit them in all of their classes.

This notion is what brought Jewel Adams to the Free Press’ door over eight years ago. A longtime south side resident, Adams remembers Simpson Street kids “always had books in their hands,” and she was impressed by their professionalism. Students clock in and out each day and carry business cards.

Adams said her son, a talented athlete, struggled in math but lacked the confidence to ask for help. She said Simpson Street was one of the only after-school programs in the neighborhood she could find with an academic focus.

“It’s fun to have something going on in the gym for sports, but we need more academics for our kids,” Adams said. “When it came down to getting him that material (for school) I had to run to Simpson Street Free Press for it.”

Eight years later, it’s summer of 2017 and I’m one of the editors who does these ‘multiple rounds.’ I work with all kinds of students, customizing my lesson plans to their interests and learning styles, and I’ve also become a little bit of an expert on out-of-school time literature. I can recite the mission statement in my sleep. I have spoken and written publicly to reporters, elected officials, citizens, and parents, representing the Free Press.

Eight years later, it’s summer of 2017 and I’m one of the editors who does these ‘multiple rounds.’ I work with all kinds of students, customizing my lesson plans to their interests and learning styles, and I’ve also become a little bit of an expert on out-of-school time literature. I can recite the mission statement in my sleep. I have spoken and written publicly to reporters, elected officials, citizens, and parents, representing the Free Press.

When I started at the Free Press, I was scared to death of “networking” with people, and truth be told, I’m still sometimes terrified, but I know how to do it, and I do it everyday.

Today I’m in New York, pursuing a Master in Fine Arts in Writing and Activism. It’s the most populous city in the United States—or so I wrote in my postcard to the students.

Geography is an ongoing lesson plan at the Free Press, maps adorning the walls of the newly-expanded Monona newsroom. Jim Kramer, the organization’s executive director calls maps “learning portals.” We find them particularly helpful when working with students, who (like me) are more responsive to visual stimuli, when taking in information.

New York is the perfect place for someone like me—a writer, musician, stand-up comic, who considers herself an activist. When I started at the Free Press, I was scared to death of “networking” with people, and truth be told, I’m still sometimes terrified, but I know how to do it, and I do it everyday.

The other day, I checked my Brooklyn mailbox on the way to a show, and found a large envelope in the mail— a new issue of the Free Press!— filled with fresh articles in English and in Spanish, about big, smart, important topics like Geography, Space Science, Energy and the Environment, and a beautiful editorial about representation of people of color in literature that I assigned while working closely with a brilliant middle-schooler named Kadjata Bah.

Reading through the paper, I remembered the first time I read the paper in my middle school library. Reading it, I experienced the kind of joy you can only get from learning something new, and understanding the world a little better.

The work that has come out of SSFP is academic, it’s rigorous and it’s radical.

That first year I worked at the Free Press, I looked up to people like my friend, Jonah, who had ripped apart my school newspaper, and never shied away from a fun, interesting metaphor if it stuck with people. We traded work and improved each other’s stuff.

I met editors, like Sisi Chen, who could improve a piece of writing I thought was perfect. These same editors pushed me to share my own ideas. It was always scary, but I found that speaking up and sharing my work always felt better than not sharing it. And it got easier when other people shared, too.

Empowerment is contagious. And with this new-found empowerment, my true potential to be an effective leader in my community started to unlock. I began to see sharing not just as something I was afraid to do, but as something I couldn’t afford not to do. This continues to make all the difference.

I am so thankful to Jim Kramer, Jonah Huang, Deidre Green, Mckenna Kohlenberg, Taylor Kilgore, Ben Reddersen, Gloria Gonzalez, Claire Miller, Adaeze Okoli, Ashley Crawford, Brianna Wilson, Andrea Gilmore-Bykovskyi, Sisi Chen, Darlinne Kambwa and everyone else at Simpson Street who believed in me, sharpened me, and turned me into the sort of person who believes in herself.

Aarushi Agni (@aarushifire) is a Brooklyn-based writer, stand-up comic and musician, hailing from Madison, WI. She eavesdrops on conversations about medicine and public policy. As a comic, she’s opened for lovely people such as Aparna Nancherla, Jackie Kashian and Maggie Faris. For the last four years, she has produced and performed within Yoni Ki Baat, a yearly monologue showcase celebrating the intersectional stories of women of color. She’s also a singer/songwriter, frontperson of several bands, including Tin Can Diamonds. She founded Brown Girl Lifted in 2015.

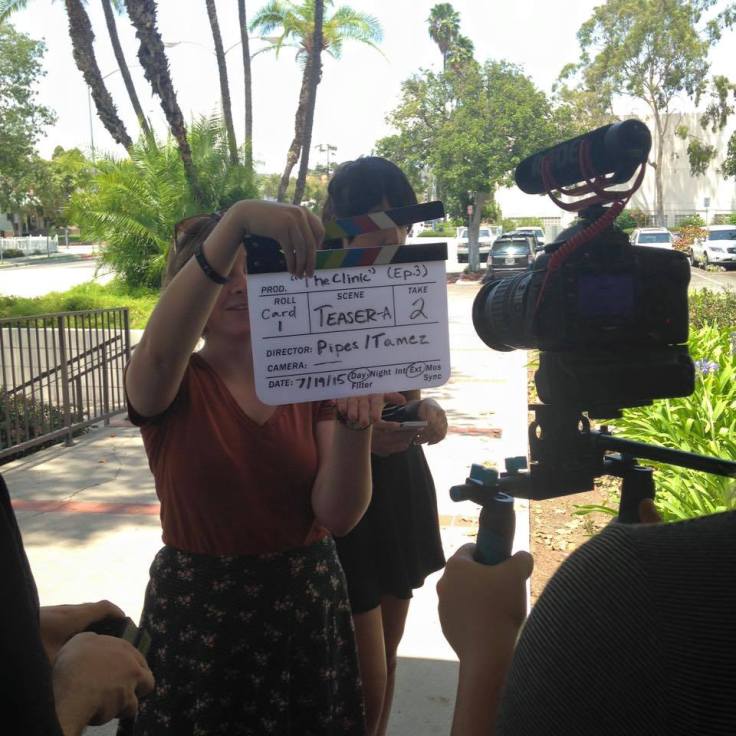

In a political reality wherein clinics like these are in real danger of having their doors closed, Meet Me @ The Clinic is a fun-size workplace comedy that is equal parts awkward and heartfelt.

In a political reality wherein clinics like these are in real danger of having their doors closed, Meet Me @ The Clinic is a fun-size workplace comedy that is equal parts awkward and heartfelt.

Today, we see activism take many online forms, from copy-and-paste status alerts containing desperate instructions, to checking in at Standing Rock, to live videos of political events and literal warfare, to 160-character death notes. Like her character, Pipes has made several videos in service of social justice

Today, we see activism take many online forms, from copy-and-paste status alerts containing desperate instructions, to checking in at Standing Rock, to live videos of political events and literal warfare, to 160-character death notes. Like her character, Pipes has made several videos in service of social justice

The Clinic was filmed for free in various locations, including the Western Justice Center, where Pipes had worked.

The Clinic was filmed for free in various locations, including the Western Justice Center, where Pipes had worked.

Dave Chappelle tells a rape joke and my boyfriend stifles a laugh

Dave Chappelle tells a rape joke and my boyfriend stifles a laugh

I’m a first generation African American. Not an African-American, but an African American. My parents were the first members of my family to arrive in America. Although I am by every legal definition an “African-American” man, I don’t fit the social and behavioral molds Black people fit in the American cultural imagination. According to others, I don’t act like “black.” This has at times made me feel as if I was standing on a racial periphery. Certain parts of the black culture simply don’t apply to me.

Even though I don’t consider the history of African-Americans to be my own, learning how they were treated in the United States was fascinating and appalling. It disgusted me that a group of people so marginalized were forced into building up the very systems that sought to oppress them. After empathizing with that painful history, I started to step inside the periphery.

I am shaken and puzzled by the use of one of the most controversial and infamous words in American English—“nigger.”

This was a word that has many meanings: property, worthless, animal, object, inhuman, garbage, criminal, prey; it was and is still used to keep the proverbial boot on the necks of black men, women, and children. In contrast, decades ago some members of the black community turned the word into a term of endearment. The modified term nigga also has many meanings: buddy, friend, brother, cool guy, understanding guy, trusted individual. So now we there are two words with very different meanings. In regards to my experiences and racial identity, I never fully stepped into the center of the black perimeter until those words were used to describe me.

I remember in elementary school, my friend, Omar who fit the stereotypical black mold addressed me as “my nigga.” Without fully understanding the term, I felt accepted. I was proud to be acknowledged as black. After this experience, I found myself using the word frequently to describe myself and my friends, not knowing the entire time that I was swinging a double-edged sword.

Years later, near the end of my senior year, I invited one of my newer friends to go with my group of friends to our senior prom. My newer friend was a Southeast Asian who was very open-minded and loved all cultures, and respected the urban and black cultures. When I picked her up from her aunt’s house, she told me it was very important that I not be seen by any members of her family. The week after prom, she told me that her aunt had seen me and told her father, who told her, “Not to hang around dirty niggers because they could be selling drugs.”

Before I heard her repeat those words, I had always considered the word nigger offensive, but I’d always brushed it off as a relic used by incompetent, uneducated, bigoted, stubborn white people. It wasn’t until that label was slapped on me that I felt it. And it stung like hell. And oddly enough, that was the moment that I truly felt “black.”

So what does “being black” mean for people like me?

I was born in the United States, but spent two of my formative years in West Africa. I returned at the age of four and knowing only my Ivorian culture. I’ve always known what it means to be African—proud, moral, and strong.

Being African American is harder to make sense of, but I am beginning to understand what it means for me. Being black means having resilience—possessing both the same stature and fortitude as cockroach for centuries. Being black means being precarious. One word, one action, one misstep and everything can be taken from you by those who are waiting for you to fall back on old stereotypes. Being black means being ambitious. Although society sometimes says otherwise; no man is born wanting to be a slave, and many who have been denied success want their place at the top. Lastly, being black means being fragmented—broken but not destroyed.

On a daily basis, African-Americans have their images shattered and put back together again—by celebrities, by real-life experiences, and by that big bad wolf we call the media. When I was first called “a nigger,”I realized that in someone else’s mind I fit the mold: jobless, violent, incompetent, and short-sided. Funny thing is, I didn’t fit any of those descriptions, and although I was angry, my dark sense of humor couldn’t help itself. I had had my image broken, and felt the urge to piece it back together by, well, being myself. I suddenly needed to sway a person I’d never met and would probably never meet against his own prejudices, just like many African-Americans are forced to do each day, especially with that cancerous word still floating around. A relationship in which one party is working to appease another party who lacks any concern for the former’s well-being, improvement, or any suffering caused by them. Do you know what to call a relationship like that? Slavery.

Now that that uncomfortable conversation is over, how about we answer a question that it could’ve lead to: what does it mean to be white?

The derivation of man-made ideology and cultural practices is fascinating, isn’t it? While keeping in mind that the allegorical polarity between black and white is often pulled into real life, we still don’t understand that this is very dangerous. Or, we’ve been warned but we just don’t care.

It might surprise some folks to know that the word “white” is used as somewhat of a slur against people of color. Since elementary school, I’ve heard my black friends use it to describe another person of color, usually with an annoyed, impressed, or comical tone: “He looks so white!”

In high school, one of my oldest friends, Tasha once described her first impression of me. It started out as flattering….”I remember thinking that you looked cute–but then you opened your mouth and started talking so that went away.”

Confused, I asked her why, to which she responded, “You sounded so white. You used all these big proper words; you sounded like Uncle Phil from the Fresh Prince.”Other than feeling a little self-conscious, I didn’t know how to respond to her. She did however, make a point of saying “That’s how you’re gonna be!” whenever we watched the Fresh Prince and the Uncle Phil character came on-screen.

As a slur, the word “white” has several forms and implied synonyms: boujie, uppity, oreo, Uncle-Tom, etc. All of these words are meant to describe a person of color who aspires to be proper, intelligent, graceful, and eloquent. These traits are included in white stereotypes, and aren’t negative. But despite both “black” and “white” traits being built on inaccurate assumptions, anyone who steps outside of the racial perimeter can sometimes be singled out and ridiculed.

Being white is sometimes seen as the polar opposite of being black, and it keeps both “races” from learning more about one another, leaving little room to be malleable. I’ve been called white several times by my peers because of my interests in stereotypical “white” culture and my lack of knowledge concerning “black” culture. Something as simple as liking the band Linkin Park or not having seen the movie Friday was started an orchestra of sneers and gasps of misbelief. There are times when being called white cuts deeper than any other insult, and why? Because without warning, you can once again find yourself in that lonely void I call the racial periphery.

Nigger and “white” should’ve never existed, but somehow we’re too proud to let go of them. Despite all of our talk about acceptance, tolerance, and the ‘melting pot,’ some parts of our society hold on to words that allow room for distinction. All Americans are entitled to “liberty and justice for all” but has the dream been fulfilled?

Speech is used to keep people in chains that they don’t have the key to. Do we like the word nigger? Many Americans would say no. But if we took away the word and replaced it with something less painful to describe African-Americans…say “ghetto,” the two words would possess the same implied meaning. Is it fun to use the word “white” to make fun of our black peers? I can only speak for myself but yes it is or has been. Do I and other blacks like that that word is associated with mostly positive traits? A number of us would say no.

Yes, we are bound by the words we use to describe each other due to the historical and societal implications of those words. But the sweet, dark irony of it is that we choose to accept those implications. We choose to accept that nigger is black and black is bad. We choose to accept that goodness is whiteness and therefore goodness is bad. So then, as citizens of the world, I believe we’re left with two options when it comes to these slurs: redefine them or forget them.

Eleazar Wawa is an African who also happens to be an American, who appreciates and honors his identities the best he can. Wawa dedicates his professional life to mentoring, teaching, and encouraging kids so they can create their own paths in life. While he doesn’t currently call himself a ‘social justice crusader’ at this point, we’ll see what the future holds.